Trying To Swing The Pendulum A Bit Less

Training, as we know it, has become strength training for many climbers. Not climbing training, but rather getting some of the parts of force development a bit stronger. It's an easy slope to slip down. I fear we are going to see more people "Frankensteining" their training—trying to make the parts stronger one at a time—than stepping back and trying to get better at the craft.

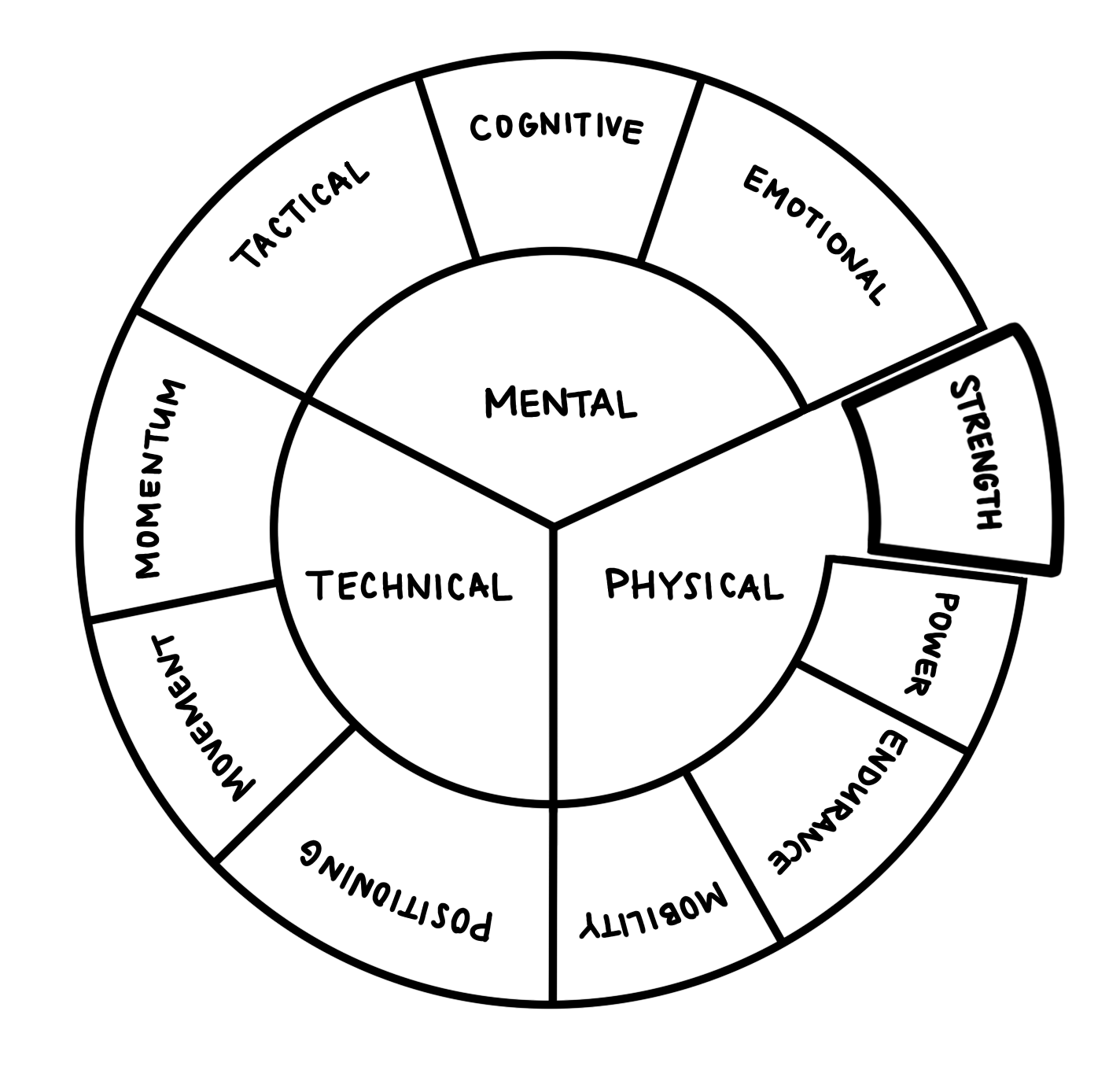

Last month I taught a course on "Strength Training for Climbers" at a CWA event in Calgary, and I tried to make this point. Using the CS Performance Wheel above, I tried to emphasize that strength was just a small part of preparation.

I also underscored that most of us are already really strong, far up and right on the curve of adaptation in many of our numbers. Even an average rock climber is probably in the top 10% of humans when it comes to grip and pulling strength.

What this means is that the hours we spend trying to get our half-crimp even stronger on a 20mm pull, and doing so by pulling a block off the floor since our shoulders are providing too much feedback that the loading is dangerously high, might be better spent in another part of the wheel.

The problem is that the other parts of the wheel are not as tangible. Not as easy to measure. Not covered in the most popular climbing assessments…and for good reason. Strength gains are easy to measure, where tactical improvements, movement skill, and timing are terribly hard to measure. It’s as if we somehow believe that were we to get to a certain level of pure strength, all else would fall to the wayside.

This is no different than an endurance athlete chasing VO2 max numbers or a Crossfitter chasing a faster WOD time. These numbers convince us of our fitness, whether performance improvement happens or not.

I wonder if an athlete did a simple self-assessment whether they could see the picture clearly. What if we asked a few simple questions?

- When I fail on a climb or boulder, is everything perfect from my positioning, to my footwork, to my timing, to my sequencing, leaving only my finger strength as a potential limiter?

- Do I legitimately need to be able to do lock-offs on a pull-up bar in order to send my goal routes or boulders?

- Am I equally adept at all wall angles, hold types, and movement styles, or is there something that sticks out as a limiter?

- In my weekly breakdown of hours, am I spending focused time in each of the areas in the Performance Wheel? Am I ignoring a major group completely? Am I evenly spreading time across the physical portion itself, or sticking with just strength?

- Am I the strongest in the gym at ______, yet not the one doing the hardest climbing?

Look, I am a huge fan of building strong athletes, and call myself a strength coach before personal trainer or gym owner. I believe that every single one of us needs to pursue greater overall strength, all the time. And yet, I feel it is foolish to train too specifically, too much of the time.

Strength training is rewarding in that we get to push numbers all the time. Hip positioning, not so much. Mobility drills, even worse. And yet our biggest gains often come from mindset shifts, learning to use our legs differently, or getting better at reading positions.

I think the key is to help people learn to address different parts of performance in a conscious and progressive manner. It's about understanding what "work" looks like in not just strength, but mobility, cognition, and momentum.

I believe there are clear progressions and cycles to all of these facets of the game. I think there's way more to it than the (relatively simple) advice of just doing more climbing…there has to be. Most of us simply can't throw more hours into the gym. Instead, we need to level up our attention and discipline, and really look at what is holding us back.

So, yes, do your block pulls. In between, think deeply and consider the last time pulling straight arm on an excellent hold really limited you. If you’re hung up at the same performance level from last year or the year before, I hate to be the one to tell you—the training is wrong. The good news is this: I’ve never met an athlete that was truly plateaued. If we can find the thing to fix, we can get the ball rolling again.

.png)