When I first sit down with a new athlete and we start to talk about getting to the next level, coming back from an injury, or prepping for some big objective, the conversation has to start with what they are doing right now. It also has to include talking about what they did to get to their best-ever performance. It was a hard lesson to learn, but I’ve come to realize that most of us already have the “bones” of an excellent program somewhere in our own training history.

Years ago, I would start each new athlete on my “ideal program.” It was laid out in a detailed spreadsheet, based on a dozen books and a dozen years of my own training. I would suggest that the athlete try to conform to this plan, as it had worked so well for me. Some could and some could not follow the plan. If they could not follow it, I had this feeling that there was some problem with the person. After all, the program was really well thought out!

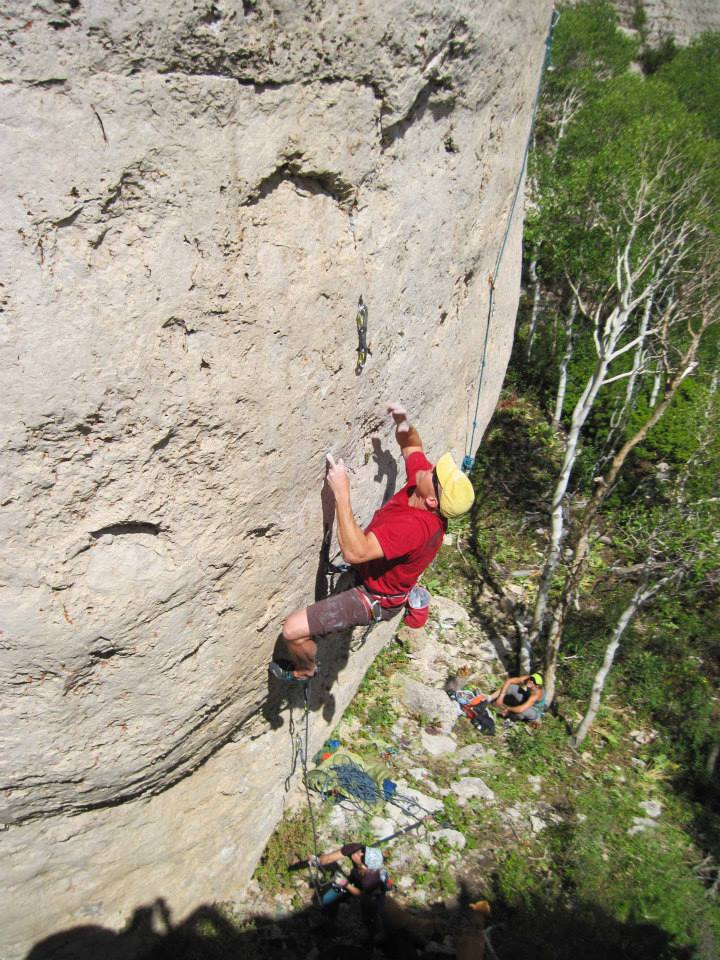

As I grew in my coaching practice, I came to learn that athletes could succeed on any number of plans or training tactics. In fact, if you take a cross-section of the world’s best in any discipline within climbing, you’ll see that each person trains quite differently than the next. It’s no wonder a “Path to 5.12 Plan” only works for maybe one in 20 people that buy it. Thus, having a clear picture of what each part of our training program is supposed to do becomes essential.

For those of us that are engaged in trying to become better, we start to learn about and perhaps adopt new tactics and exercises. We start to do this warm-up, that hangboard plan, this exercise in the weight room. We add and try and experiment and add some more. It’s no wonder that each of us ends up with these wildly different things in our sessions! Add to this our specific needs: therapy movements, addressing weaknesses, available tools…and we can end up with some really crazy workouts.

My mentor, Steve Petro, incorporated a heavy piece of 2” thick steel rod into several parts of his training, simply because he had it laying around. I used to use a 16 pound shot put for warm-ups. Almost every climber these days seems to have and use a mobile hangboard, and tries to come up with useful and relevant ways to use it. And sometimes, unique things really work. We add and add and add exercises, and eventually feel like we have a good program, limited only by a lack of time to do even more!

And then the issue comes down to usefulness. When we have thirty exercises to do in a week, how do we determine which ones should be emphasized? Which ones are useless? Which ones are highest-risk?

There are things that are habit, things that are fun, and things that really help. The best way I’ve found to sort through all of this is to do an audit every few months. I like to do this alongside a quarterly testing time. The audit has three parts:

- REVIEW: During the review, we go back through our training logs and look at each individual session for quality and enjoyment. Ask basic questions like:

- Did I enjoy the training?

- Did I see progress across the training cycle in this session?

- Did I progress the exercises in a way that addresses a specific need in my climbing?

- REVISE: During this part of the audit, we take time to make changes to the upcoming plan. Here, we need to eliminate or change exercises that are not progressing. We also need to set forth planned progressions for the new exercises. An essential part of this revision is to try to strip things down to the most essential components. It is easy to build in way too many exercises and too many desired adaptations. It's my recommendation that a seasoned athlete only pursue progress in one or two exercises, and seek only one adaptation, such as greater strength OR greater endurance OR better recovery, not AND, AND, AND…

- REBUILD: This part of the audit is when you write out your upcoming training. This is the final phase of editing, and often, even after years of training, I will still find something that can be cleaned up or eliminated. Each session should have a starting point that is clear in terms of load, exercises, and volume. Each should also have a clear direction of progress, such as “add load” or “add minutes.”

A good way of getting things down to the essential is to test how you are performing on each of the exercises you’re doing and the facet of fitness you’re trying to get from it. For example, if you’re pursuing lockoff strength, test it out in a performance environment (climb or boulder) and then dump the lockoffs from your workouts. Go back to the performance environment a couple of times the next month and see if the ability (locking off on climbs) is dropping off. If your performance declines, add some specific training back in. If not, chase other, greater needs.

Sometimes we need a clean slate. Once a year, I suggest you do something that seems a little crazy: Dump everything. This is a really simple exercise in that you simply eliminate all supplemental training and go back to just climbing. Do this for a few weeks and try to get a feel for where you really need more help. Don't just assume you need greater finger strength or leg strength or core strength. Instead, look at the parts of performance that are starting to show up as limiters. Perhaps you need to do a little bit of shoulder strengthening to help that joint feel more stable. Perhaps a little bit of mobility work will make your hip positioning easier. Maybe, after a hard session, a little bit of general cardiovascular training would help you recover better.

Whatever it is, add it back in slowly.

Go back to what worked for you in that past “best ever” season. The program won’t work exactly as well as before, but hints about session durations, climbing volume, and style of training will help you get on track. “Better” is always better than “more.”

Don't just do exercises because you have the tools for them. Don't do exercises because somebody else is doing them and they look cool. Human beings are physically pretty weak, but mentally incredibly adept. If you're going to get the most out of your body, start by using your head.