by Steve Bechtel

There is a trap in training. You start to train and you feel it working. You push more and the results come. A little more strength here, a feeling of power there. Yet the longer you train, the harder it is to feel those gains. They come, and each time you are grateful that it’s still working. If you are psyched to get better, you keep after it. The trap, it turns out, is that we lose sight of why we started. We get so absorbed in the gym progress that we forget to walk out the door, drive up to the hills, and get after it.

Think about this for a moment: If you could build out a schedule that allowed you to do whatever you want whenever you wanted, what would that look like? For many of us, it would look like several climbing days a week and spending only as much time doing supporting work as possible. For others of us, we might really enjoy the process of building strength in the gym, and only want to go out and climb occasionally. It doesn't really matter which is your preference, but it does matter that your behaviors match these preferences. The issue, as I said above, is that many of us spend time longing for the outdoors and focus our hours on simply trying to be better prepared for those few moments we get out there.

Many of us have the misplaced idea that performance can only come a couple of times a year for a brief few weeks. Much of this idea comes from the early writing on climbing training and program design, which, in turn, was pulled from sports like track and field or endurance, running or weightlifting, where the athletes were seeking to perform during scheduled times of the year for short periods. In short, we built an assumption on our performance based on some early writers' misunderstanding of how high skill performance might look.

Moving to Performance

Variation of training works. Even if you start with a very simple off-season/in-season structure, you’ll find that your body responds well to the change. When we move from preparation to performance, we not only get to do more of what we started out to do, but we also get to see if that preparation was appropriate.

If your off-season training cycle in the gym was three days of hard bouldering and strength, you probably wouldn’t have the juice for a lot of time out at the crag. The ultimate goal when we switch to a performance period is to stop pursuing improvement in the gym, period. We do just enough mobility work. We do just enough strength so the numbers don’t fall off, but we’re not pushing them up. We leave the gym every day feeling like we could go out and climb right after the session.

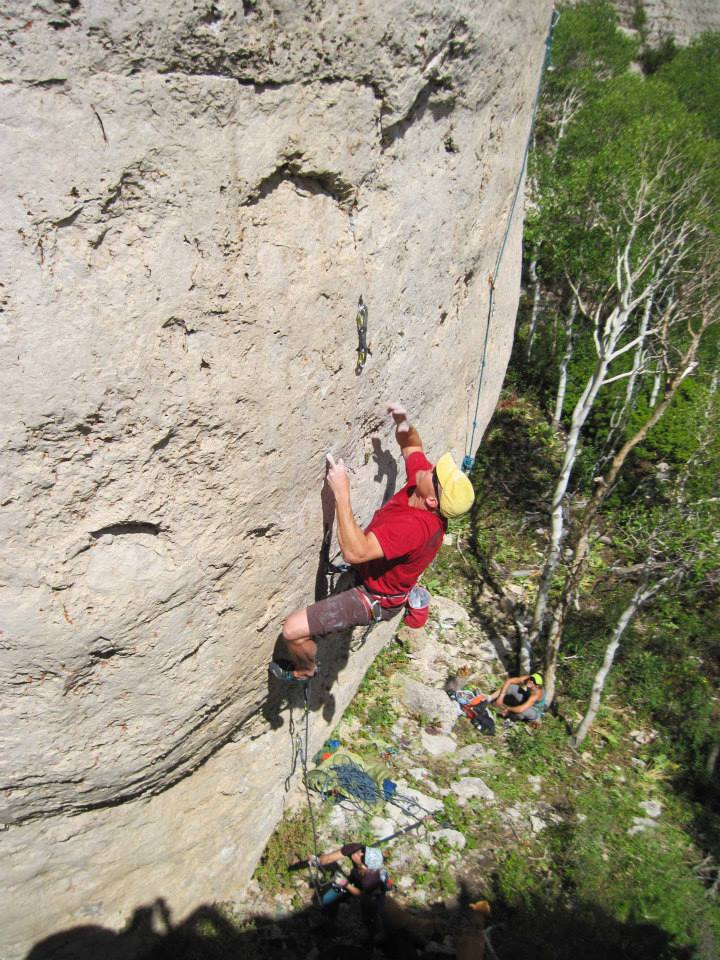

At the cliff, we give everything to performance. There is no base-building, weeks of volume days, or toproping. We enter the performance environment and we do the best we can. If you’re wondering what the performance environment is, it’s hard efforts that require your full attention. It is maximal or close to maximal grade climbing, limit level onsighting, and a very occasional day of maintaining some volume or lower-intensity effort.

A typical climber can perform at high levels for somewhere between one and 3 months. When you start to decline in your performances, or you start to feel on the edge of injury, you can gracefully back off for a week or so, and then get going, or you can end the cycle.

If you choose the latter, take that same week off, write out some notes on what did and did not work, and plan your next off-season's training.

Flipping The Switch

Moving into performance mode, or declaring it “go time” is not easy for the training lover. We long for the regularly scheduled sessions, the familiarity, the crawl toward progress. None of this is nearly as clean at the crag.

For most climbers, simply acknowledging that it is Go Time is the needed mental switch. Like I said, there is comfort in grinding it out in the gym, but that is not what most of us declare we want out of all of this. There are some important differences between training time and performing time, and we should not muddle the two. It’s way too easy to be trying your project AND going into the gym in the hope of getting even more strength.

In-Season Off-Season

Recover to be ready for sending Recover to be ready for training days

Maintain medium-high loads / grades in the gym Push loads in the gym

Give full efforts at the crag Climb enough to stay sharp, but no projects

Gym volume is limited Gym volume is maximized

Goals have to do with integrating skills Goals have to do with isolating skills

A simple way of thinking about this is to build out your obvious seasons for best climbing, or for trips, or for comps. What times of the year are you going to want to be at your best? What times of the year does the weather, life schedule, or work mean that training might be a better option.

It is my belief that 7-9 months of the year should be dedicated to performance for most climbers. This might be structured with a training month followed by two performance months, in a cyclic manner 4 times a year. We can also structure a longer training phase in a winter off season, say two months, followed by 3-4 months of performance before a summer strength rebuild. The fall would then be performance-oriented.

The exact schedule of training versus performance periods.

The main skill we are trying to develop is switching our brains from training mode into performance mode and back, but on large cycles rather than on an “as-desired” basis. There is so much possibility out there for the climber that can’t differentiate between these two modes: it might change the game completely.