If You Can't Say "Yes" To An Adventure Tomorrow, Why Not?

One of the hallmarks of being a functional human is the ability to do normal tasks. This includes carrying things, going up and down hills, moving heavy objects, moving over or under obstacles, and more. We also need to be able to do these things at high levels of effort occasionally, as well as do them at low intensities for long duration from time to time.

You can imagine that our bodies have adapted to this sort of activity over many millenia of hunting and gathering…luckily we’re early enough in the sit-on-the-couch-and-look-at-phone-for-hours era that none of us have genetically adapted to it. For optimum health and fitness, movement is a key ingredient.

We all tend to have a propensity to be better at certain facets of movement than others, but it doesn't release us from the job completely. The problem most adults run into is that they specialize, then specialize further, then specialize to the detriment of all other qualities. To some degree, specialization is OK, such as doing more bouldering than route climbing, but when we train ourselves to be functionally inept at something that is a basic quality of human movement, we've stepped over the line.

As a young climber, I spent my first couple of years climbing at areas where you'd base out of the car—the parking was just a stone's throw from the cliff. 2-3 years later, when I first went to the main wall at Sinks Canyon, I was beat up by the 400-foot vertical gain, 10 minute long hike to the crag the first couple of days.

It happened again a year or two later when my friend Bobby and I first ventured into the backcountry for a weekend of alpine climbing. The 5.8 cracks were well below my limit at the crag, but after a 10 mile hike, poor sleep, different food, and a 1,500-foot talus scramble, felt like the hardest climbing in the world. How in the world, I wondered, would I climb harder routes out there?

As I ventured through the Exercise Science program at the University of Wyoming, I looked at everything I learned through the lens of my climbing. How does this apply to finger strength? How does this apply to handling a pump? Why do I climb so poorly after a long hike? Is there a way to be “good enough” at all this stuff?

Much of exercise science is aimed at solving discrete problems in training and sport. As I learned more about this, and more about the sports we were studying, it became apparent that we could not take lessons directly from these sports into the sport of climbing. The number of different skills, energy systems, and strength qualities required by climbing are beyond almost any other sport.

We need endurance and strength, power and mobility, calm and arousal. What I started to learn is that the more eggs I put in one basket, the better that basket...and the weaker the others. A strength-focused season left me stiff and with no stamina. Increasing my endurance time saw strength slip away.

People, we've got finite eggs. Training is about compromise, not about balance. And yet, there is a more essential lesson: holding onto any fitness quality is much less challenging than developing it in the first place. The hack, or the secret, or the workaround, or whatever you want to call it, is in the consistent maintenance of developed physical qualities.

Building Versus Maintaining

The solution comes in the form of understanding that maintaining a fitness quality requires much less effort than developing one.

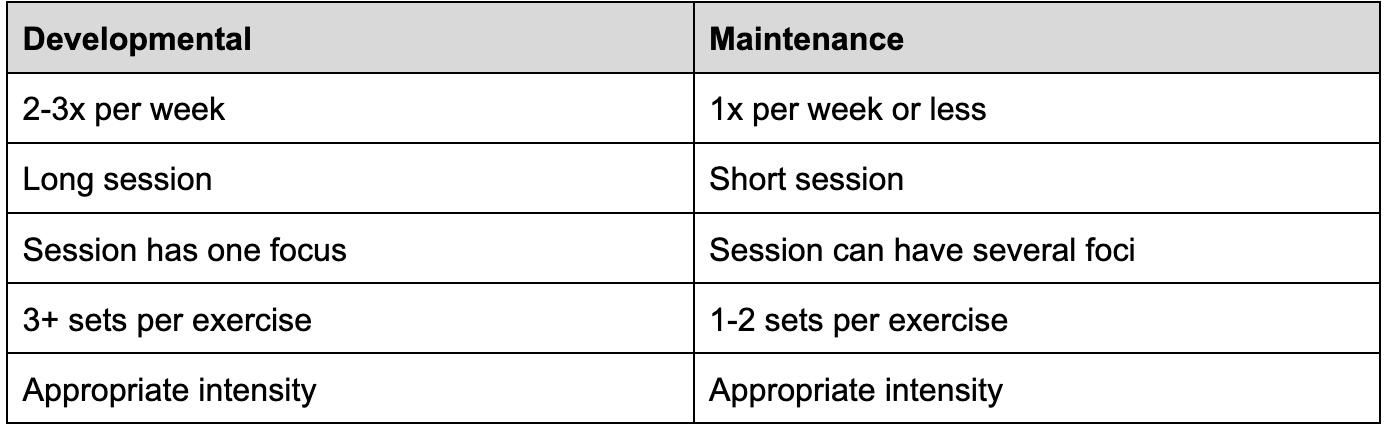

There are some general guidelines to the loading and intensity of both types of loads. They are as follows:

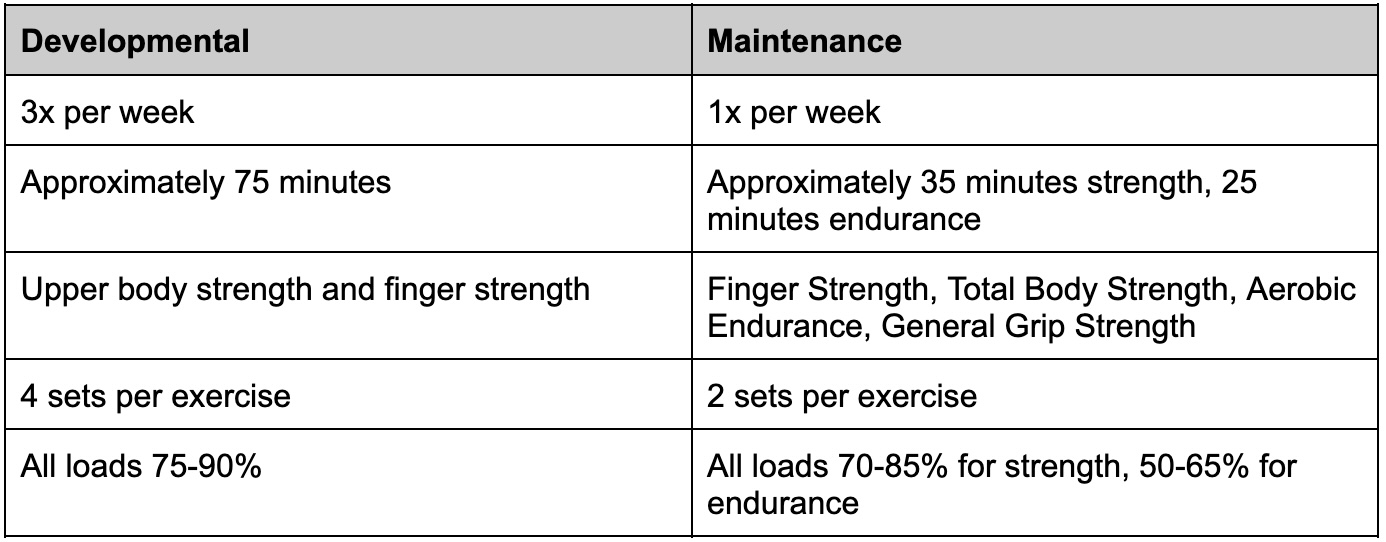

Let me give you a more concrete example. We’ll look at the difference between a strength session done in a developmental phase versus a maintenance phase.

Strength / Finger Strength Session:

By harnessing a good mindset toward what you can and should be developing in any session/season/phase, you reduce a lot of training stress, both physically and mentally. If you feel like you can manage to develop all of your areas of fitness simultaneously, I have good news for you...it can get even better if you focus.

What is Maintenance, Really?

Most of us have a really clear understanding of what developmental loading is about. You pretty much just do a lot of something faster, or heavier, or longer, and you get better at it. The problem is that it takes a lot out of you to keep increasing everything, and one of the first things to go is any facet of fitness that you aren’t chasing.

In the charts above, I suggest training for maintenance once per week. What I urge you to look for is trying to keep all fitness facets somewhere above 90% of your year-best all year long. This means being ruthless in allowing yourself to train less in the areas you’re maintaining (even less than once a week). It also means experimenting with doing even less… and seeing if it still works.

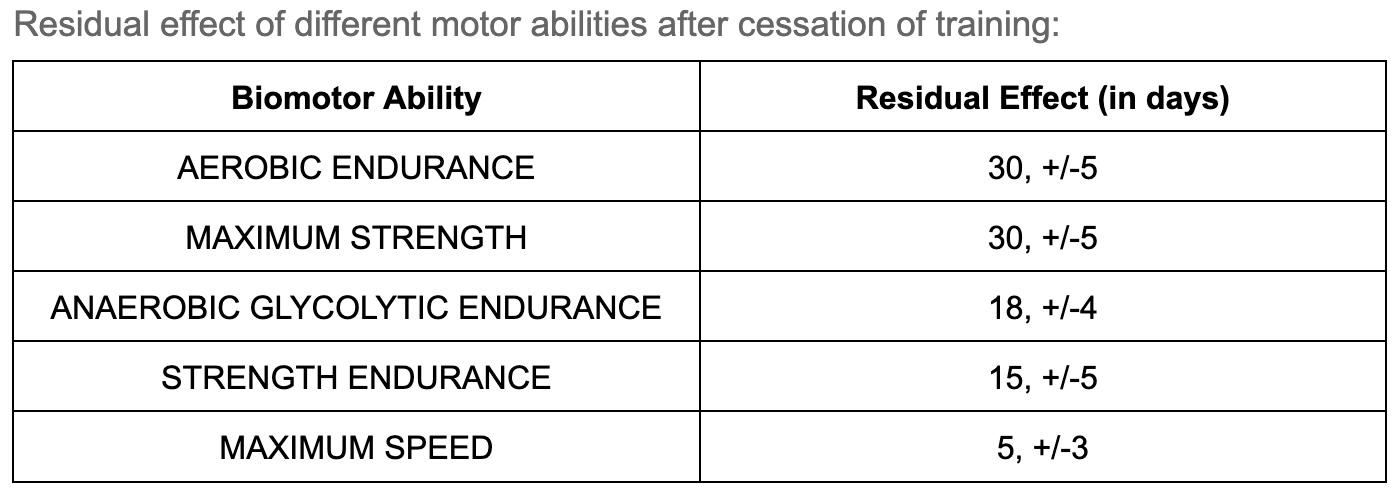

Over time, you’ll find a frequency that works for you, and this frequency might be different for different qualities of your fitness, depending on the persistence of those factors. In Karsten Jensen’s Flexible Periodization he gives us a good glimpse into about where the main facets of fitness drop off:

The take home is this: Your fitness will decline if you stop training it altogether. Stay after it, even if it is once every few weeks, and when you come back to push it again next season, you might actually get better rather than “back in shape.”

If you’re doing a good job of maintaining fitness, you can go boulder with friends any time of year and not feel like you’ve got no power. You can say “yes” to an alpine climb next weekend. Importantly, you are ready to help a friend cut firewood or move a couch or plant a garden, and still be able to climb the next day.