I think everyone can remember, on some level, the first day they came up against the limit of their endurance on a rock climb. It’s an unpleasant feeling, and you’re not altogether sure you get to use your hands again afterwards. For me, it was a marathon day of many pitches of granite cracks with a much better climber, who, by the end of the day, was doing lots of extra work himself trying to help me tram up the hard parts of the pitches.

In subsequent seasons, I’d seek out that same fatigue and eventually get in some kind of “shape” for longer pitches. The more I now understand about developing endurance, the more I see that there were a lot of parts of the process in trying to get some fitness. I also am a little regretful I didn’t seek better understanding of what was going on when I was in those building periods. I did a lot of painful work that might not have helped me all that much.

The normal method among climbers, even today, is to seek out a fatiguing climb, give it a few tries, pump out, and come back down. If they have some juice left, climbers will “burn out” on a couple of other laps and go home with a nice, satisfying burn in their arms.

And it works…mostly. It gets our fitness up and our fatigue tolerance built to a level that we can do some longer or steeper pitches. The issue is the pain we force ourselves to endure on the way to fitness, and the protracted time it takes to get it. Time, I argue, that we can shorten with better understanding of what we are pursuing.

Training is about overload and recovery. It’s about giving the body the most appropriate stimuli for change. It’s about progress. In sport, humans have pushed against the limits of endurance for generations. In the modern era, with a better eye toward what works and what does not, humans have consistently built better systems, better gear, and better training programs. The result? We’re better at literally everything in the world of sports.

One of the most profound advances in modern training is the use of interval efforts in building endurance. Many of us think we’re doing intervals in our training, but often that just ends up looking like traversing to failure, resting for as little time as possible, and then hitting it again until we fall off. I’m not sure what you’d call that, but it’s definitely not interval work.

What are intervals?

Intervals are intense exercise efforts interspersed with rest periods. Chances are you’ve done something like this in climbing, and most people have experienced it in some other form of fitness. There are lots of ways to break up exercise, but for our purpose, we need to think of intervals in terms of breaking up a desired level of effort into achievable chunks. This differs from simply going as hard as possible in an exercise or on a boulder, and then resting and going as hard as possible again. In order to get the most out of an interval-style workout, we want to set the intensity of the work quite carefully.

Until maybe 1910, runners simply developed their ability by running for long distances or by trying to run more quickly over short distances. The first well-known example of interval training came out of Finland and was the brainchild of coach Lauri Pikhala. Pikhala’s athlete, Paavo Nurmi, used interval style efforts to develop his running and had 5 gold medals at the 1924 Olympics in Paris to show for it. The intervals were not super well organized, and mostly consisted of sprints with easy jogs between.

It didn’t take long for other coaches to hop on board. In the 1930s, German coaches started prescribing “heart rate sprints.” In these, runners would sprint until their heart rate hit 180 bpm, and then they would rest until it dropped to 120 bpm. They would then repeat the interval. This is actually a brilliant and somewhat forgotten version of interval training, and although there’s nothing magical about the actual heart rate numbers, recovering until a fixed physiological point is much more effective than recovering based on time alone.

As an athlete progresses through a workout, it naturally takes longer for them to return back down to 120 bpm. By allowing for longer recoveries as the workout progresses, we seek to create a similar starting point for each hard effort. Remember, progress is the goal—not fatigue.

It wasn’t until the 1950s that Emil Zatopek brought intervals to the international spotlight. His famous method included high volumes of repeat efforts, sometimes up to 100 intervals in a workout. Zatopek took this method to the Olympics, where he won both the 5K and 10k races. Encouraged by his success, he then registered for the marathon a few days later, and won that event. It was his first time ever running that distance.

“Why should I practice running slow? I already know how to run slow. I want to learn to run fast.” -Zatopek

Again, an essential aspect of effective interval training when it comes to developing endurance, is that we’re not trying to kill ourselves on each and every interval. We’re trying to break hard work down into smaller chunks so we can do more total work per session, and eventually perform just a little better.

Why climbing is different from running

Obviously, climbing is different from running. The most important thing to keep in mind when we look at the two in comparison, is that the power output and intensity vary wildly move-for-move in climbing, where they don’t vary as much in running. Climbing is an acyclic anaerobic sport, where most running is cyclic and aerobically driven. This is a generalization, but stick with me.

We don’t really need to develop a high level of cardiorespiratory fitness for the types of efforts that we see in most bouldering and rock climbing. Instead, we need to really work on being able to bring air into the lungs (breathing as fully as possible while straining to move up rock), and we need to develop the ability to do repeated submaximal movements (by improving the local muscle and the blood supply to it).

This is why we want to lean more toward the specific, climbing-like endurance activities when we are really trying to get better. Running and cycling and other leg-focused sports are fine as recreation, but they miss out on the two main developmental aspects of climbing endurance.

Although it is a larger discussion, I will say that activities like swimming, cross-country skiing, and rowing are one step closer to what we want out of endurance. When planning aerobic-style activities that are not climbing, keep this in mind.

What Do We Want?

Intervals break down the intensity of “single efforts”—they help us find “do-able chunks” of climbing at a desired intensity. Nurmi and Zatopek, and so many since, had to first be able to do race pace, then do race pace for longer and longer distances.

We can attack endurance from both the duration and the intensity sides. If I am attempting a long and fatiguing climb, say a 40 meter 8a, I should find two starting points:

- Can I climb 40 meters at all, and at what intensity?

- Can I do the moves at the 8a level, and for how long?

Short of just spending a season trying this route, how might we develop our fitness for it? Instead of just driving out to your local crag and sieging your project for 12 weekends in a row, how might you approach it if you had to fly somewhere and try to send in a two-week trip?

An essential starting point is to have the capacity to effectively try the climb. By this, I mean you should be able to go to the cliff and have enough energy to try the moves enough times to learn. You should be able to climb enough to improve your fitness. For a climber traveling a long way to work on a project, getting two or three good tries a day is a worthy capacity goal.

Note that building excessive high-intensity endurance is not all that useful if you’re tapped out after one effort. So… first build the ability to do 5 or 6 pitches of climbing, in a day, at all.

Low-intensity climbing, then, is the base for a good route climbing day. Basically, if you can’t hike up to the crag, do a couple of warm ups, a couple of burns, and maybe a cooldown, no amount of intensity on the Kilter Board can save you. This is not a tall order. Most of us are probably already here, so we can move on to more specific work.

Once we have built capacity, then we can look at addressing specific route endurance, or the basic ability to climb a 40m pitch. You’ll have to be able to do this at a reasonably high grade before any interval program becomes worthwhile. A person hoping to climb 8a endurance is probably not going to have much success if they can’t climb 7b routes of the same type and length relatively easily.

A really common mistake is to ignore full-pitch efforts, even at more modest grades, in the thought that intensification alone will complete our preparation.

And Then It Comes To The Moves

If we can sustain a whole day of climbing and we can sustain a whole pitch of intensive climbing, it’s then important to address whether we can do the movement on our desired project or our desired level of climbing.

An important tactical skill is to accurately assess what the true performance output might be. For example, many of the steep, pumpy limestone routes in my home area are not all that hard move-for-move, so my sustained level of movement might only need to be V3 or something. Naturally, being really solid at V3 (or above) is a piece of this, but there are a surprising number of climbers I spend time with that might climb V8 on the boards but can’t put together even a couple of V3 boulders without failing.

Although we know that the moves on any climb vary considerably, let’s simplify things and say that our climb is 40 meters of sustained V2 climbing. It’s a pretty sure thing that an 8a climber can do ten 4-meter boulders graded V2, and so we can start the interval work there.

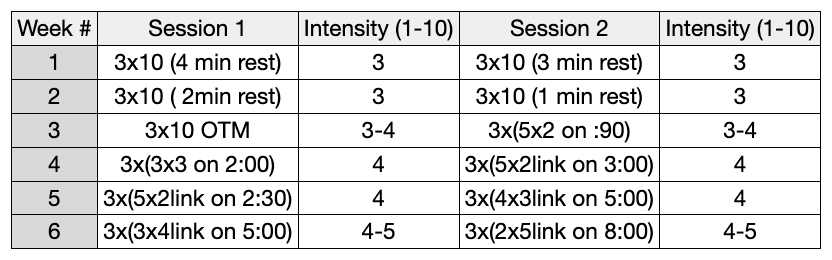

At first, we simply do the ten boulders, resting, say, 4 minutes between. We then might take a long rest, and repeat the sequence of ten boulders another time or two.

In order to build fatigue resistance, the climber might then reduce the rests to 3 minutes, then 2, and then one, and potentially do them “on-the-minute.”

This is a good first step.

A second step might be to do two back-to-back on a 90 second rolling clock, then move on to three back-to-back on a 2 minute clock. With each progression, we’re aiming to climb well and maintain an ability to avoid fatigue.

A huge key here is that to progress through a series of sessions like this will take several weeks. Long and slow progress is key to developing high levels of sustainable performance, so we can’t get in a hurry.

The athlete can then consider linking problems. On a good spraywall, we could eventually aim for 5 or 6 repeats at V2 with an open hold downclimb between. This would start to get very close to the route-specific duration and difficulty, and would represent the end of interval efforts in favor of performance intensity simulations.

How We Advance Intervals Matters

There are four main ways we advance intervals:

- We can make the single efforts harder. This is a key component of getting better at hard routes, but if endurance is our goal, we have to make sure we can do all of the intervals well. Patience and persistence are key here.

- We can make the interval efforts longer. This is what we did above. Longer sustained periods help us manage fatigue and learn efficiency. They also help our bodies adapt to sustained overloads.

- We can reduce rest. This one is dangerous as it is an easy way to feel like the training is “working better.” Popular fitness programs tend to use this method…with dubious results on performance. Any rest reduction between work efforts should be considered carefully and align with your desired outcomes.

- Increase the number of intervals. Again, think about what the goal of the training is. Do I need to do six series of intervals? Eight? If I don’t need that kind of capacity for the performance environment, I shouldn’t train it.

The big takeaway is not to “go like hell” on every effort. The aim of intervals is to take a slightly-better-than-you-are level of fitness, break it down into do-able pieces, and slowly build the ability. The goal is not to punish yourself, but to slowly coax the ability to do really hard stuff with a minimum of pain. Going too hard, for too long, too often leads to burnout. Leads to overreaching. Rarely leads to climbing the way you’d like when you’re five moves from the chains.

Finally, the biggest piece of the pie is showing up enough times to stimulate a change in the body. This is the number one failure point I run into with climbers. They try endurance workouts a couple of times, go too hard, and shrink away from the pain. The solution?

Start easy.

Keep progressing, but don’t seek pain.